That Time I Pissed into a Volcano

The results were spectacular! WRITTEN & ILLUSTRATED by PETER MOORE

Greetings, Elswhereians!

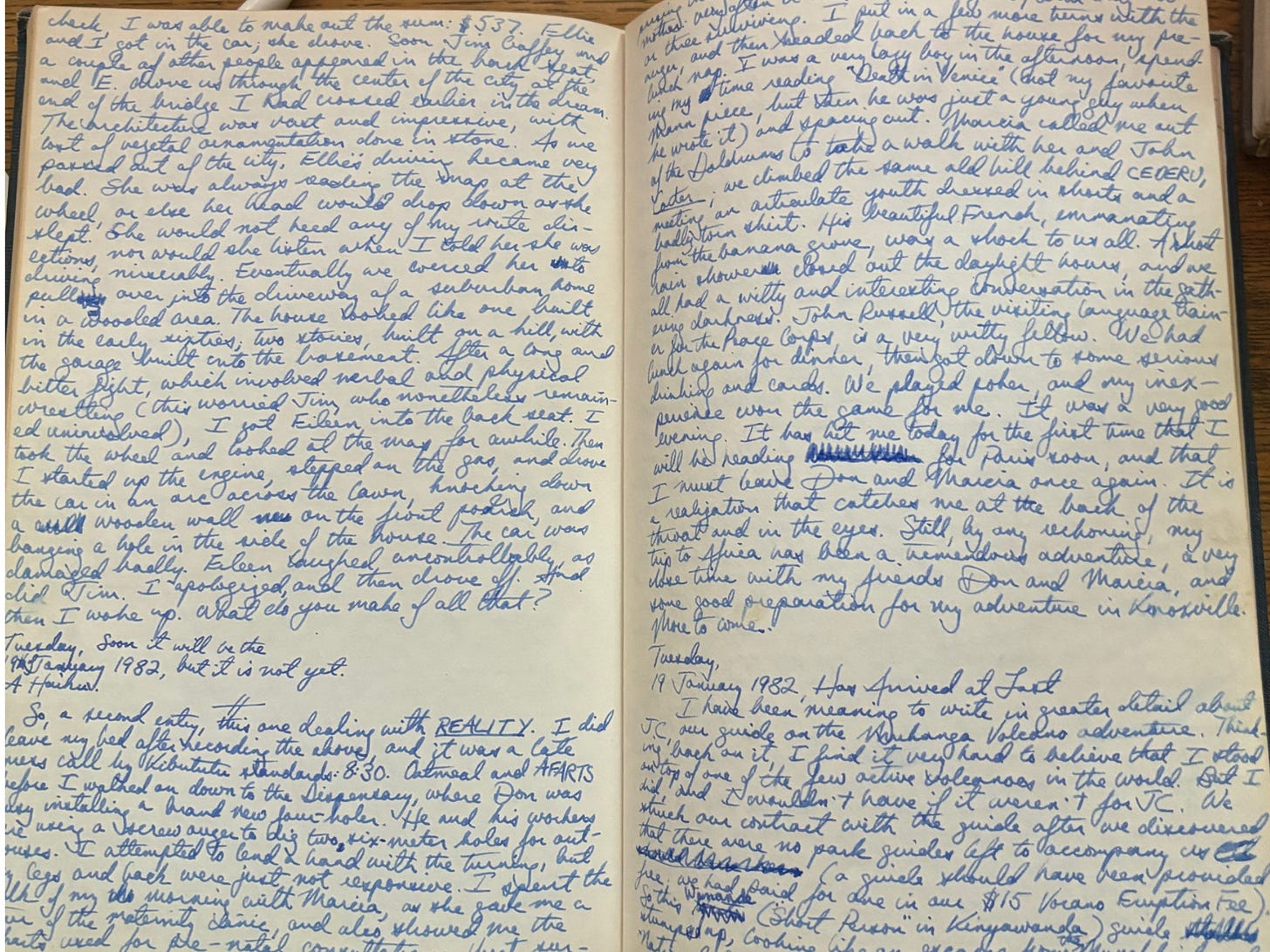

For those of you joining in late, I’ve been keeping a daily journal…oh, since the beginning of time (October 12, 1978).

I wrote about it here.

I’ve now made journal entries for 16,000+ straight days, and recorded about six million words of experience, noticing, worry, and exhilaration. My journal is a great resource for my backward glances, and I want to tap it here, and add the illustrations that will provide hectoring commentary on who I was back then, and what I think of mini-me right now.

Welcome to my recherche du temps perdu.

As Marcel Proust wrote: “Do not wait for life. Do not long for it. Be aware, always and at every moment, that the miracle is in the here and now.”

I have tried my best to live that advice from the madeleine-munching author of The Remembrance of Things Past, and my daily journal is the best reflection of my own devotion to—and failure to follow—Proust’s example.

Below, my journal entry about a visit to an erupting volcano, in eastern Congo…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Road2Elsewhere by Peter Moore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.