R2E Excerpt #54: "The chief beauty about time is that you cannot waste it in advance"

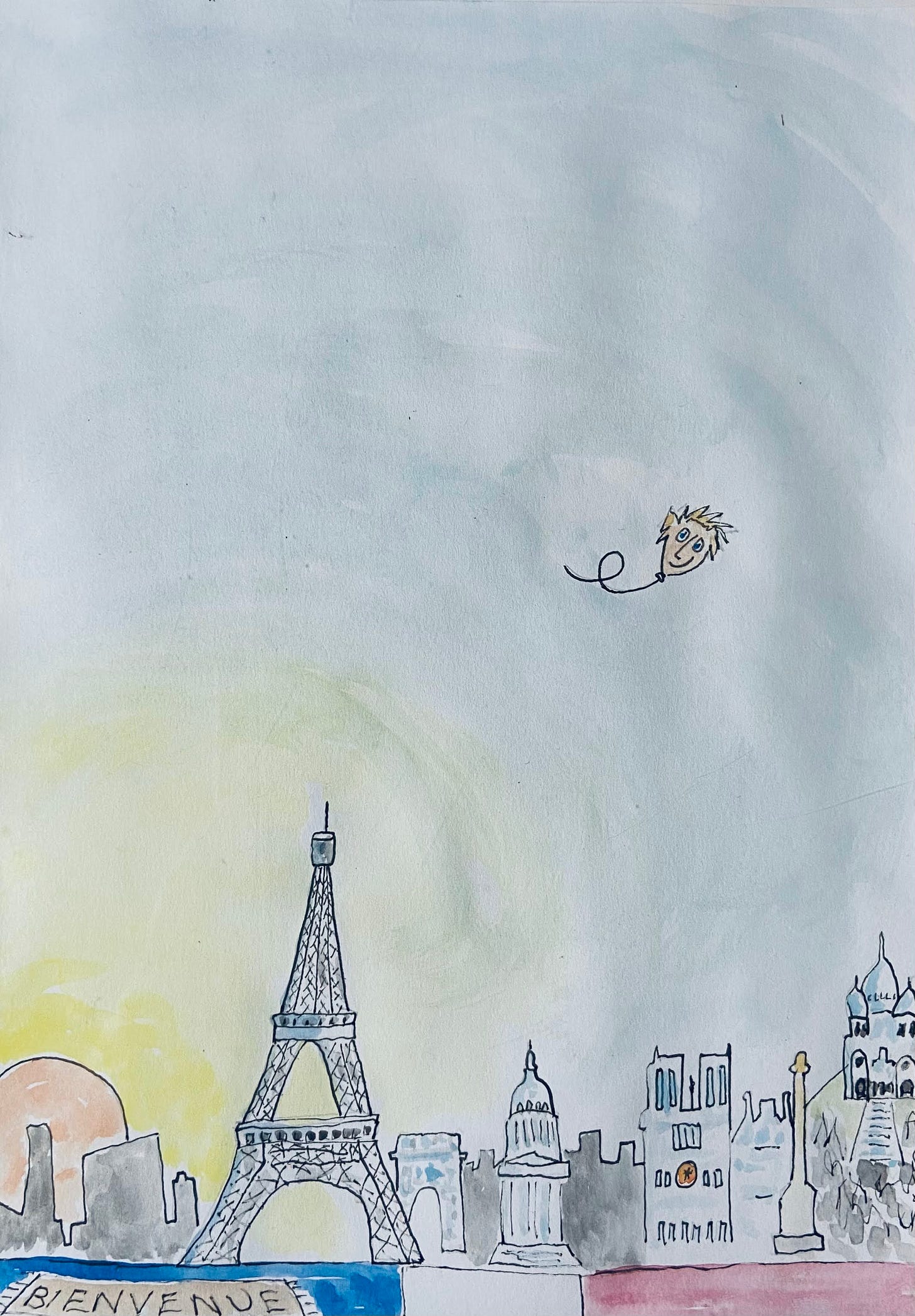

So wrote the novelist Arnold Bennett. Once, he was famous. Now he's dead. There's a beautiful lesson about time in that, too. WRITTEN & ILLUSTRATED by PETER MOORE

When the mood strikes, I run excerpts here on substack from A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG NINCOMPOOP, my coming-of-age-travel-memoir-with-funny-drawings. (The first entry is here. Most recent one is here. If you become a paid subscriber, you can access the complete archive here!) It details the story of my road through Paris, London, and god help me, Zagreb, in search of the ultimate destination: a life worth living. The story so far: Young Peter arrived in Paris, occupied a dorm room at the Alliance Française language school, tiptoed out onto the Boulevard Raspail and the Paris Metro, and made the first steps on the road to elsewhere.

Then I went to England. Big mistake. But aren’t mistakes the first step toward anyplace worth going?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Road2Elsewhere by Peter Moore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.