R2E #59: My neighbor, Virginia Woolf

We had something else in common, aside from the living in southern England: We both needed a room of our own. WRITTEN & ILLUSTRATED by PETER MOORE

When the mood strikes, I run excerpts from A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG NINCOMPOOP, my coming-of-age-travel-memoir-with-funny-drawings. (The first entry is here. Most recent one is here. If you become a paid subscriber, you can access the complete archive here!)

My memoir details my road through Paris, London, and god help me, Zagreb, in search of the ultimate destination: a life worth living. The story so far: Young Peter arrived in Paris, occupied a dorm room at the Alliance Française language school, tiptoed out onto the the Paris Metro, and roared off on the road to elsewhere. I was lost, but that’s the only way to get found, right? After Paris, I moved on to Olde England, to check out where that Shakespeare guy lived. In this excerpt, I face a crisis in lodgings in my adopted hometown—Amberley, Arundel, Sussex, England. And Virginia Woolf was too dead to help!

I WAS WAITING, I imagined, for my former English professor, Charles, and his wife Elinor, to determine the fate of my literary mission in Amberley. I had short stories to write, but I couldn’t do that outdoors in December. If they kicked me out of their house, where I was an uneasy guest, I’d have no choice but to travel to Chamonix and ski with friends, instead! But I was a Serious Artist back then, eager to deny myself pleasures while I typed my wits out. And soon I would be un-homed!

I had been considering all this while seated in my star seat high in the South Downs.

But while I was up there, a third option had developed.

Soon I was walking down a country lane, my minimal luggage in hand, to a low, ramshackle home that looked as if it might be sinking into the Wild Brooks, a swampy declivity in the south of England. I knocked on a wooden door shrouded in honeysuckle, and waited a bit. Then I knocked again, and waited some more.

At last, Helga Brunner slowly swung the door open. She regarded my bags suspiciously, as I introduced myself. She was perhaps 5’4” tall, and clearly becoming shorter every minute. My hopes now rested on a kindly gnome whose home smelled of age and apples.

Helga was an artist, and the home/studio she invited me into was filled with a lifetime of brushwork. Her canvases were large abstracts and florals, and her productivity had exceeded the market for her works. She gestured for me to follow her, and showed me into a 10’ by 10’ room filled with her paintings, and illuminated by a picture window that framed a wild tangle. The garden too was a kind of abstract art, with tendrils strangling roses and death commingling with rampant growth. This room smelled like oil paint, Helga’s preferred medium, and it looked like creative chaos—the product of a mind too busy to find homes for all her brainchildren.

“Will this work for a room to write in?,” she asked in a crackling, sprightly voice. Her blue eyes were striking and teary; her skin deeply creased from a lifetime of expressiveness. “We can shift these paintings.”

I was set back. She was only offering me a chair to sit in. But now that my professor and his family were at home, I actually needed a place to, um, stay.

“Charles and Elinor mentioned that, maybe, I could stay here for the next month?,” I ventured, feeling every bit as pushy and demanding as I sounded.

“Oh!” exclaimed Helga, who apparently hadn’t been expecting a lodger. But her eyes eventually brightened. “Help me move these things out!”

She pointed, I lifted, and the paintings migrated to her light-filled main studio, which had enough artwork to crowd several retrospectives at the Tate. As I moved the art, I uncovered a monastic bed, a scarred wooden table and creaky chair, and a kerosene heater.

A room of one’s own!

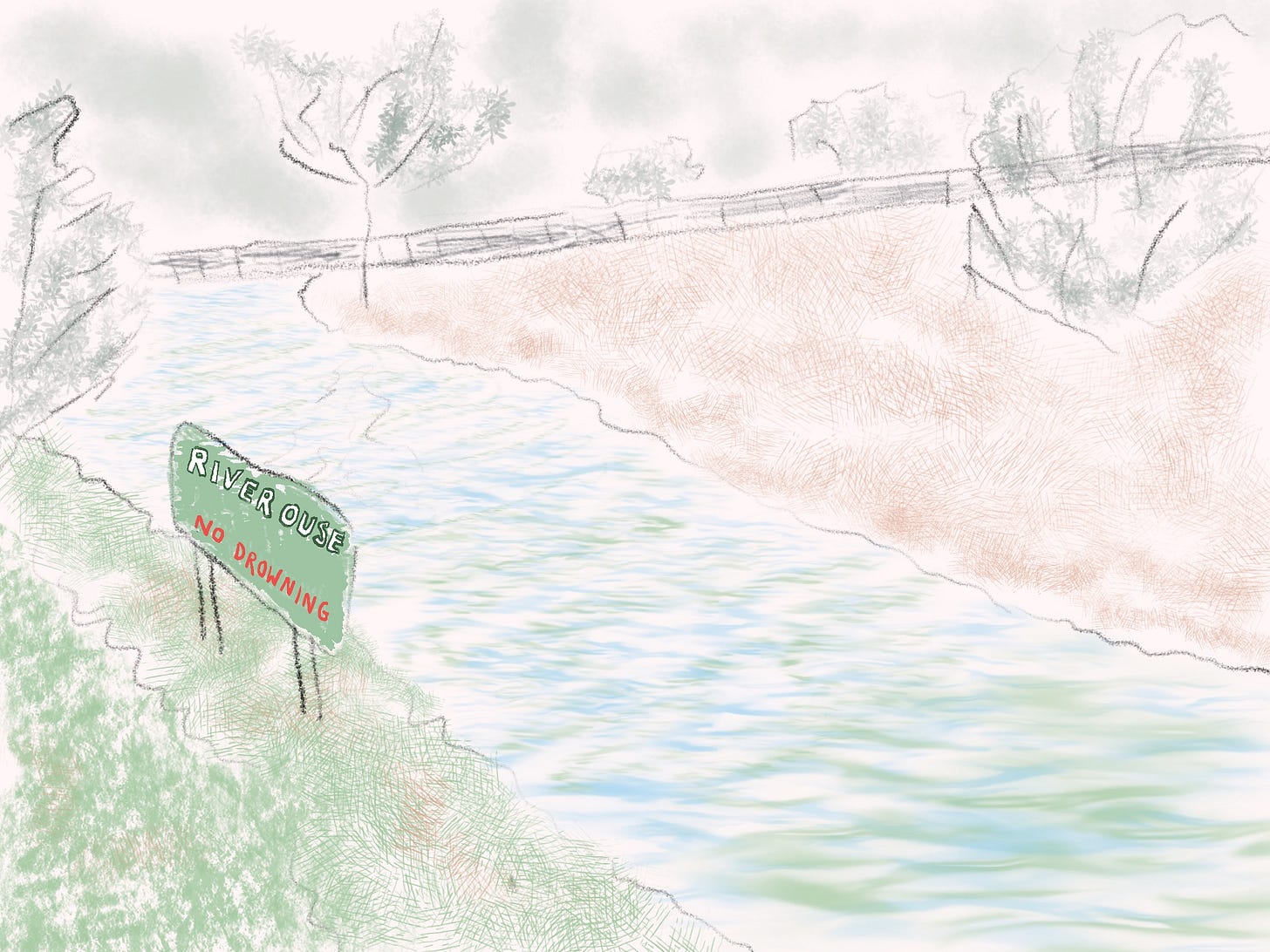

However dead Virginia Woolf might have been, she was now my near neighbor, as well, in the tiny East Sussex town of Rodmel, just off the South Downs Way. That wee burg is three quarters of a mile west from the River Ouse, where the author drowned herself during a bi-polar flare up. She and her husband Leonard Woolf had moved to Sussex four decades before my arrival, when two of their Bloomsbury homes were damaged in German bombing runs. A year after moving to Monk’s House, Woolf went for a walk. She removed her hat, dropped her cane, and walked into the Ouse, which snuffed her spark. Her body floated downstream, and it wasn’t found, nor her death confirmed, until three weeks later, when some schoolchildren happened upon it.

She was cremated and buried on the grounds of Monk’s House, under the final words from The Waves: “Against you I fling myself, unvanquished and unyielding, O Death! The waves broke on the shore.”

Had I known about her gravesite, I would have gone, and I would have probably read The Waves sacramentally while sitting on the banks of the Ouse, and shed a few self-dramatizing tears, even. But part of my arrogance at that time was my feeling that I was beyond tourism. I was focussed on raw experience—wind in hair, rain on skin, beer in belly—so I couldn’t be bothered collecting trinkets.

In her closing passage in A Room of One’s Own, Woolf wrote about Shakespeare’s little sister Judith, who died before she could enter the Shakespeare family business: Literary Immortality, Inc.

“My belief,” Woolf wrote, “is that if we live another century or so...and have five hundred [£] a year each of us and rooms of our own...if we look past Milton’s bogey, for no human being should shut out the view; if we face the fact...that we go alone and that our relation is to the world of reality and not only to the world of men and women, then the opportunity will come and the dead poet who was Shakespeare’s sister will put on the body which she has so often laid down...I maintain that she would come if we worked for her, and that so to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile.”

What’s up with “Milton’s bogey”?

Woolf failed to clarify her exact meaning during her lifetime. Given the bogey’s position in that paragraph, it’s probably a stand-in for the way Dead White Males blot out vagina-driven literary striving, especially because their penile reputations continue to be curated by the Surviving White Males. Or maybe Milton’s bogey was Adam, who as God’s favorite was in a position to set Eve aside and blame her for everything. Or the bogey could be the Bible’s false representation of Eve herself, in league with the devil, dangling apples spiked with Knowledge, and thus to be resisted at the bookstore and the poetry reading, and covered by the waves of the River Ouse.

Helga was just that sort of dangerous female: a slinger of apples and goodness. We set up housekeeping, as I commenced my labors and she steeped in her lifetime of work. Mid-afternoons she would twinkle into my room, interrupting my labors (thank God) with the gracious question: “Care for a cuppa?” I always said “yes,” and soon she would return with a crockery soup bowl filled with a pint of milk tea, and pull a lumpy apple out of her cardigan pocket. That accounted for the fruity waft of her place: The harvest was all around her.

There was a gnarled apple tree in her weedy yard, hanging heavy with unsightly specimens, the ground littered with windfall. Her tangled acre shared that aspect with her studio, with unfinished canvases leaning against huge completed works, and sculptures facing off in different directions—physically, and aesthetically. I didn’t have the eyes or bank account to buy one—plus no place to hang anything, including my hat—but I see now how perfect her example was: Keep on creating no matter what.

I still haven’t skied Chamonix.

“Women have served all these centuries as looking glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.”

― Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Looking to find more great newsletters, where you (probably) found this one? Click this link! You get cool things to read, I get cold hard cash from the guy who runs the Refind.com. Everybody wins!

Or, just help pay for my lodgings, which as you can see, has been an issue for me.

Many thanks for joining me on the Road2Elsewhere.

Great drawing. That’s all I understood regarding Virginia’s writings!

I am HERE for the Virginia Woolf content! And the very fun drawings! :)